He forwarded to me an email with the infographic above and a link to an article entitled The New Normal in Sales: Customer Dysfunction.

What did I think? What’s the impact on my customer’s business and how should that inform how his sales organization should engage with their customers?

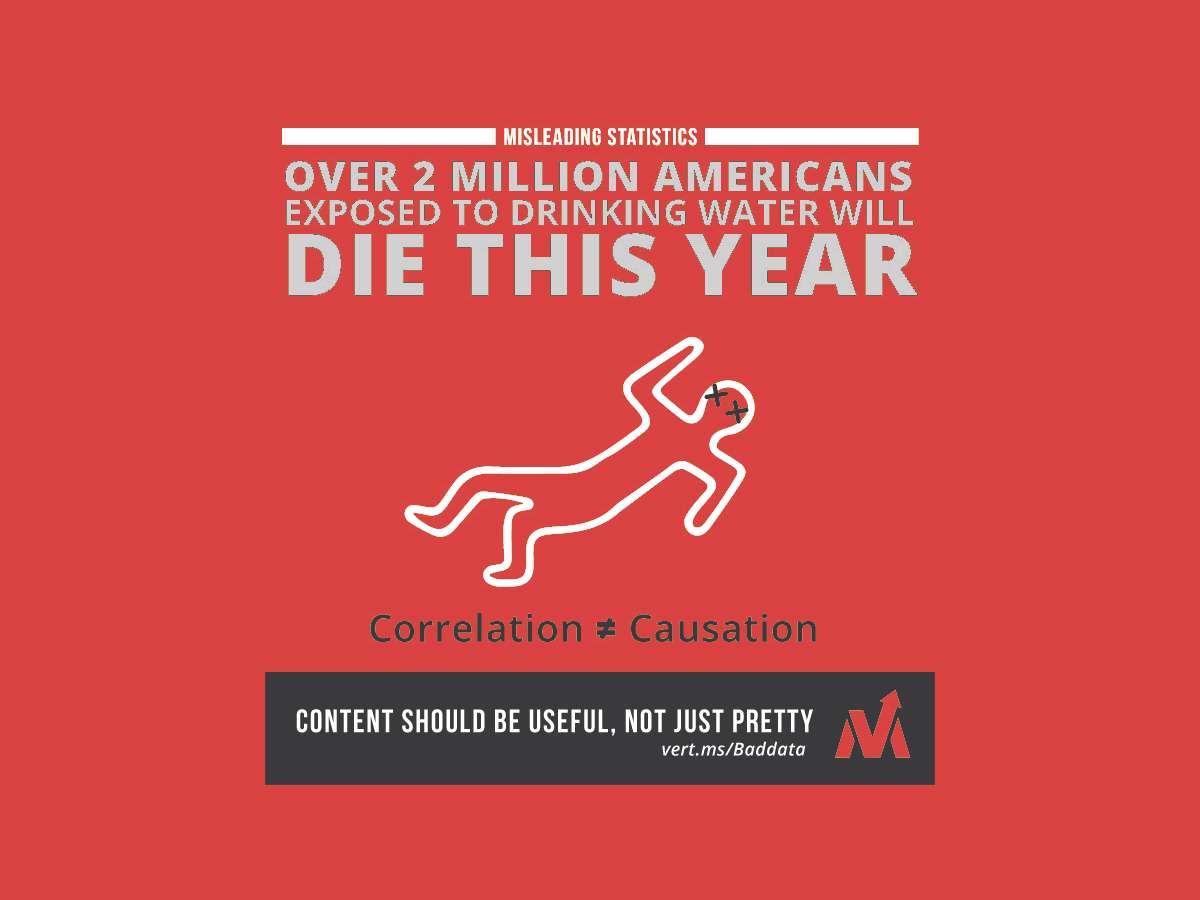

As with any statistic, to determine its relevance to you, the important factors to consider are (a) the context and scope of the research to ascertain its applicability to your business and (b) assuming that the research is both applicable and valid, to understand the ‘why’ behind the number – what is causing a change if indeed there is one. Without a deep assessment of both of these factors, the statistic (as a compass for change) is worthless. It can be dangerous leading to you to take actions that are uninformed and may be at odd with you best interest.

I write about this in my recent AI book Tomorrow | Today: How AI Impacts How We Work, Live, and Think and refer to this problem as the Trust Quandary. You can’t trust any data- or statistics- based advice unless the underlying research methodology / algorithm is completely transparency and contextually descriptive.

I will shortly get to the specific question about the reported increase in the number of stakeholders, but first I would like to elaborate on the core issue of statistics-based advice and the potential damage that can ensue.

Let’s take, for example, the other, and possible more (in)famous statistic from CEB, the 57% number. Based on an announcement from CEB, the idea that has taken hold in the market that all buyers are 57% through their buying process before they reach out to a supplier, and consequently the only remaining differentiator is price. That, of course, is nonsense. In the first instance the 57% number as announced by CEB was an average number, and the context of the research was lost in the subsequent hyperbole in the market. It is clear that a buyer who is buying paper for their Xerox copier will behave differently that a buyer who is looking to purchase an ERP system to run their business.

Context matters.

But in some quarters, sellers are throwing their hands up in the air citing this 57% as a reason why they can only compete on price, and disclaiming their responsibility to understand the customer’s business problem and discover where they might have Unique Business Value to bring to the customer.

This is misinformed, lazy or dangerous; or all three. I wrote about how you should respond in my ebook Battling the 57%: Deconstructing the Buyer-Seller Dance.

The reality of course is that some buyers are 57%+ through their buying process before they connect with a seller. Others want to engage a seller early in their buying process to learn, get advice, find a strategic business partner and do all of the things that smart buyers do. But the statistic has been misleading. In a recent post, Nick Toman of CEB has said as much.

Indeed, many pundits have interpreted our finding that the average customer is 57% through their purchase before engaging a supplier as an indicator of this trend [the death of sales]. But that interpretation is based on the (faulty) assumption that the customer actually “got it right” throughout their research. It assumes the customer stakeholders were in agreement on their problem — and their course of action — when they reached out to the supplier. To put it bluntly: this isn’t the norm.

Nick Toman, CEB

According to our own primary research; Inside the Mind of the Buyer: The Buyer / Seller Value Index – a study of 1200 buyers and sellers – 63% of buyers want sellers to engage early in the buying cycle – according to the buyers. (The irony of using more statistics to support my argument is not lost on me, but I hope you will find the research report transparent and contextually descriptive.)

But back to my customer’s question. What about this increase in the number of buying stakeholders from 5.4 to 6.8? Let’s talk a first about the 5.4 figure and then consider the meaning of the move to 6.8.

Once again context matters. In most large complex enterprise B2B sales/purchases, the buying group comprises many more than half a dozen stakeholders. For those buying copier paper, the number in the buying group is rarely more than one.

CEB talks about ‘averages’ and I’m not sure how if that is helpful. It would be more instructive if the notion of ‘average’ was replaced with the concept of ‘typical’.

For example, if we were told that; for companies in the Communications and Media industry who are buying high impact solutions, that cost in excess of $500,000 the typical buying group consists of 13 stakeholders, then that is something that a seller can work with.

That’s not to say that the CEB research is without value – I have huge respect for all of the many CEB people that I have met – but I think their market is underserved when their research becomes the equivalent of bumper-sticker pronouncements.

Before we consider the meaning of the 6.8 number we should be clear that the only meaningful takeaway from the original research from which the 5.4 statistic emerged is that there are multiple buyers involved in many buyer groups. For those who have been selling to enterprises for any period of time, that is not a surprise.

(In many cases I have seen complex buying groups who comprise more than 25 to 40 individuals who have actual material influence over the buying decision.) In Enterprise B2B Sales there are typically multiple buyers involved in a buying group and it’s up to the seller or the account team to work out who they are and then develop the appropriate relationship strategies in each case. I wrote about that extensively in my book Account Planning in Salesforce.

Assuming that CEB’s research measuring the size of the buying group is valid; broad, cross-industry and comprising a reasonable large sample-size (n>=500 companies), then we should give some thought to why bigger groups are growing in size.

From my perspective this type of change is usually driven by macro-economic factors. Undoubtedly we are living in a complex world that is consistently growing in complexity. Market segments are growing and dying faster than ever before. Just a few years ago Gamification was a big deal – but that market has almost died. Big data and predictive analytics were the key drivers of IT spend in 2013/2014, and while there is still much activity in this area, the hoopla has died down and many vendors have retrenched or died.

The Business Performance Benchmark Study suggests this year’s big disruptive factor is Digital Transformation.

In 2017 Artificial Intelligence seems to be on everyone’s ‘must-do-some-of-that’ list.

Change is constant and rapid. The compression of market cycles is just one of the macro-factors that lead to increased pressure on companies to find markets in which they can compete, and the pressure to make the right decision brings added scrutiny to major buying decisions.

One of the indicators that I monitor to assess complexity of buying environment is M&A activity. In the early stages of a merger, when companies are coming together, the focus shifts from external growth related initiatives to internal alignment and restructure. More opinions, approvals, and decision makers are needed to start projects or approve budget spend. As you see from this chart, M&A activity has continued to grow in recent years.

M&A is just one disruptive factor. Currency volatility, changes in political landscape in the US and Europe are further areas of concern. The rapid advance of AI, the changing demographic landscape, the rise of the thumb generation – those consumers who run their lives through their smartphones – and the uncertainty caused by the constant global threat of terrorism are each topics that businesses have to first understand, and then consider the implications for their business. (Read Business Performance Benchmark Study to get an overview of the strategic issues for 2017).

As these areas become more disparate, and change velocity continues upwards, then it is understandable that buying groups in large enterprises buying complex products that have material impact on their organization might need to grow to accommodate such complexity.

At the end of all of this, I ask myself does it all mean to my customer and what can I recommend. Change is constant in many respects. What does not change however are the core principles of effective enterprise selling. People matter. Problems matter.

When you understand the business problems that business people have, and you can bring value to those people to solve those problems; then you can win.

To respond to the increased velocity and the broadening of the buyer groups you need to look to technology to increase the velocity of your response and the quality of the insights you can bring to your customers. (Read: Connect Solutions to Customer Problems).

There is one final point that I think is worth making: Respect matters.

Consultants, researchers, or pundits who comment on the buyer/seller interaction, should take care not to be disrespectful of the buyers. Phrases like ‘the Dysfunctional Customer’ or ‘Buyer Dysfunction’ are not warranted and don’t do anything to bridge the trust gap that exists between the buying and selling community. Please stop.

If you want to read more of my blogs please Subscribe to Think for a Living.

Follow me on Twitter or connect on LinkedIn. I want you to agree or disagree with me, but most of all: I want you to bring passion to the conversation.